Clean water in the United States is largely taken for granted. In one of the most economically prosperous countries in the world, this isn’t a surprise. But water quality remains a concern as violations around the country are on the rise. New regulations create spikes in violations and local governments are falling behind. This is most extreme in low income and rural areas where there isn’t the financial capacity to meet regulatory updates.

The latest major regulatory changes have been around Disinfection By-Products, or DBPs. Interestingly, and to illustrate the point, DBPs have been featured in pop culture recently with videos and articles popping up across the web explaining the floating shade balls installed in the LA reservoir in 2015.

A Winning Example

Popular YouTuber Veritasium, who frequently posts about and explains science and engineering topics, has garnered nearly 50 million views on his video titled, Why Are 96,000,000 Black Balls on This Reservoir?

These black balls have one job, they prevent the sun’s rays from interacting with the treated water in LA reservoir to create high levels of bromate, a carcinogen. The bromate was forming as sunlight, chlorine, and naturally occurring bromide mixed. Since the LA reservoir is treated water that is exposed to sunlight all day long, all year long, the problem was a big concern. They solved it by using the shade balls – 96 million of them at $0.36 each and a total cost of $34.5 million.

This was a win for water quality and the people of LA. However, many low-income and/or rural areas in the U.S are not so fortunate. In fact, DBP violations have been particularly difficult for them to solve with access to few infrastructure or process improvements.

The Funding Gap

PNAS.org in their report titled, National Trends in Drinking Water Quality Violations shows that “low-income rural areas have a larger compliance gap than higher-income rural areas. DBP violations account for much of this gap. Differences between rural and suburban areas became pronounced and statistically significant after new DBP rules in the early 2000s.”

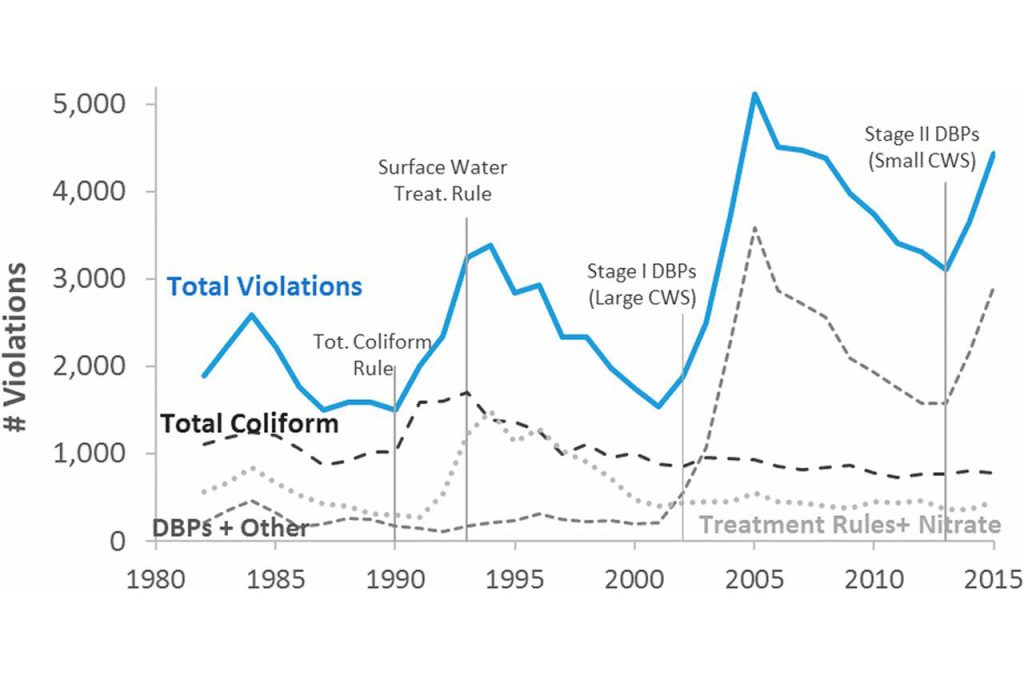

These graphs come directly from the PNAS report. As we see in Figure 1 below, violations spiked in the early 2000s and again a decade later when staged DBP regulations became effective.

Water Violations by Type and Community

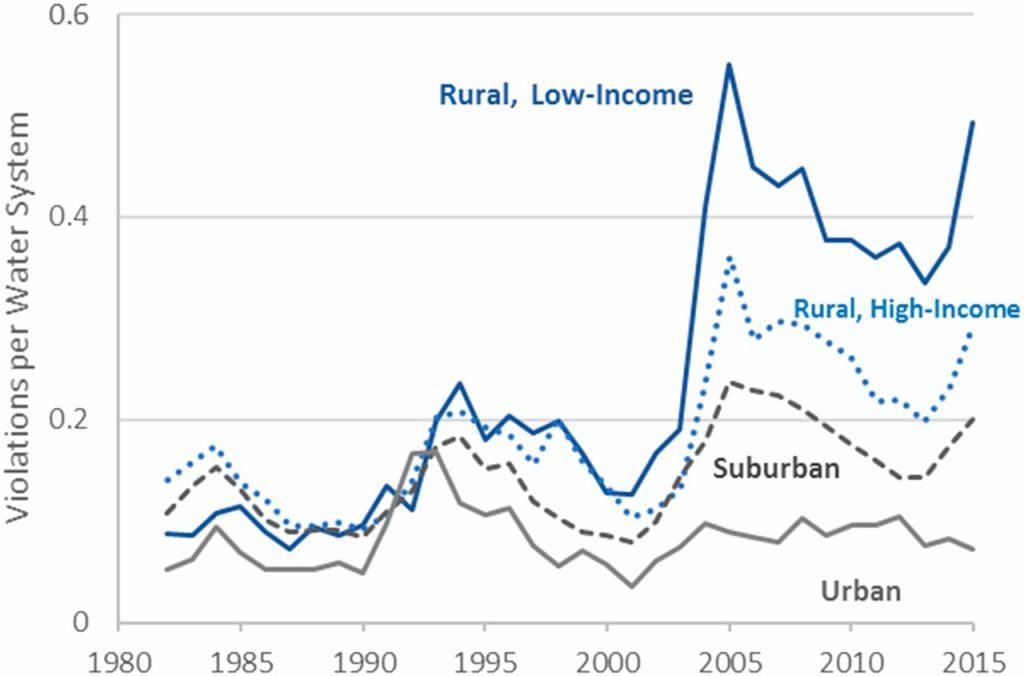

In Figure 2, we see the divide between urban and rural communities and their ability to maintain water quality and adjust to incoming regulations. The spikes in DBP violations are clearly associated with rural communities. Of course, correlation is not causation. But as we’ve seen repeatedly, budget restrictions are predictive of water quality violations.

Flint The Harbinger

Nowhere was this more apparent than in Flint, MI, where a cascade of problems quickly overwhelmed the community shortly after the debt-ridden, poverty-stricken municipality came under state control. In an effort to save money while they built a more permanent solution, state appointees decided to pump water from the Flint River instead of buying it from Detroit.

The polluted water source combined with aging lead pipes and insufficient treatment created the perfect storm. Lead content in the water spiked. From their first water samples in 2015, Flint Water Study reports that “Flint’s 90 percentile lead value is 25 ppb in our survey” which is 10 ppb above the level allowed by the EPA of 15. They even recorded several samples that exceeded 100 ppb.

As if that wasn’t enough, they experienced the 3rd largest Legionnaires’ disease outbreak in recorded U.S. history with at least 87 people infected and 12 dead. The foul-smelling tap water was wreaking havoc on many residents. It took years of legal battles for the resilient citizens of Flint to get the state to ship in bottled water and eventually switch the water source back to Detroit. While the situation has improved and many lead pipes have been replaced, the cost has been and will continue to be staggering.

The water crisis in Flint is a harbinger of things to come.

An Expensive Challenge

In Flint, the poor water quality was so extreme that the residents were able to get the legal action and political pressure they needed to make some improvements, though there is still work to be done. But in rural communities all over the U.S., under-treated water remains overlooked.

Fitch Ratings estimated it would cost up to $50 billion to replace lead service lines throughout the country, while the American Bar Association estimates that giving rural communities the treatment systems they need “would require $190 billion of investment in the coming decades.” They add that “In 2019, just $2.8 billion was allocated through appropriations for all water infrastructure projects nationwide – less than half of a percent of the amount of investment the EPA estimates is needed.”

Additionally, the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) gave America’s infrastructure a D+ on its 2017 Infrastructure Report Card. Drinking water, specifically, was given a D, citing aging pipes throughout America and for small systems, the lack of “financial, managerial, and technical capacity, which can lead to problems of meeting Safe Drinking Water Act standards.”

The Case for Simplicity

While the slow march of regulations is helping to uncover our national water crisis, the frenzied pace of technological advancements needs to solve the problems we find along the way. They’re not perfect, but the shade balls used in the LA reservoir are a good example of problem solving technology.

The shade balls are also a good example of finding simple solutions. Great engineering will focus on the simplest, most efficient way to solve any given problem. Key to the funding gap at the heart of our water crisis, simple and efficient also tends to cost much less. While governing bodies need to find more funding, rural and low income community water systems will have to rely heavily on finding low costs ways to effectively and efficiently improve their water quality.

A Rural Case Study In Simple Solutions

That’s exactly what happened in Denison, TX. This small community of 20,000 residents has an average household income that’s about $16,000 below the national average. So it makes sense that when the local water plant needed a SCADA upgrade they put it off as long as they could. But when it became necessary, they gritted their teeth and dutifully scraped together a budget of $100,000.

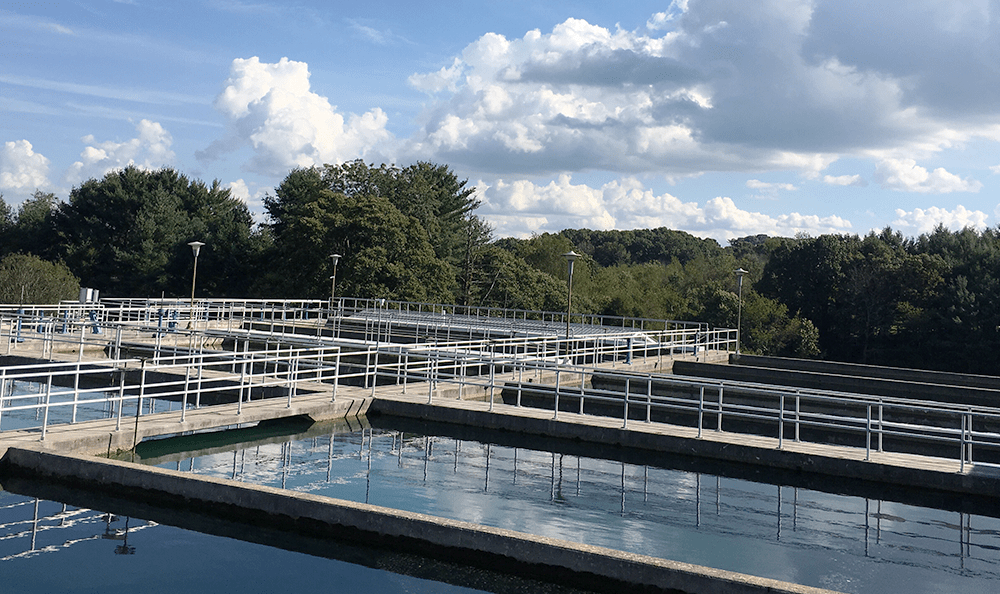

The Randell Water Treatment Plant serves Denison, TX and is located northwest of town near their reservoir. The facility is rated for 12.8 Million Gallons Per Day (MGD) and was running on older PLCs that the city couldn’t program. Whenever changes were needed, they had to pay a ladder-logic programmer from out of town to make the trip. Maintenance was both time consuming and expensive. Water Plant Superintendent, Angus Evans, knew there had to be a better way.

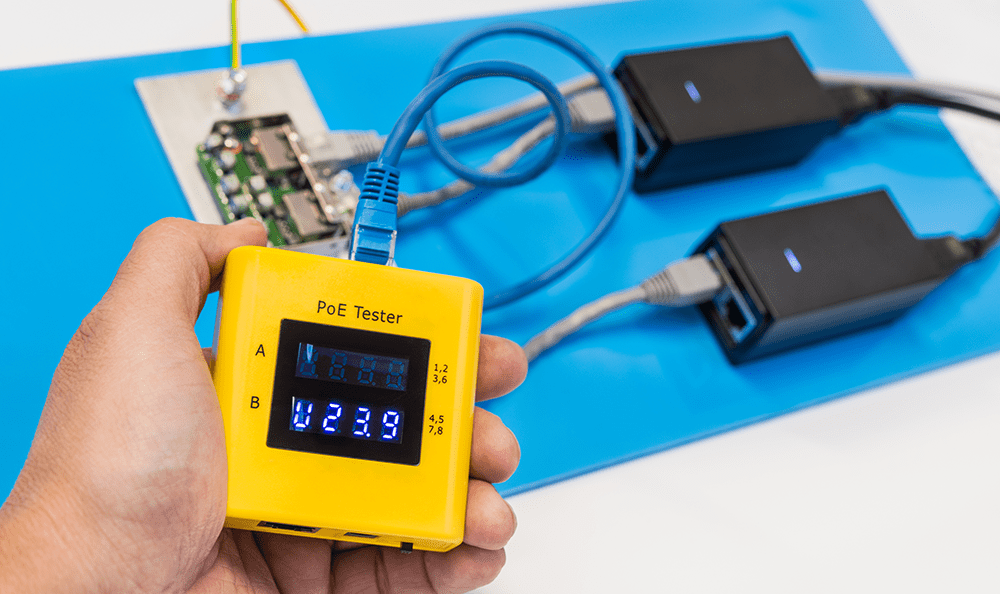

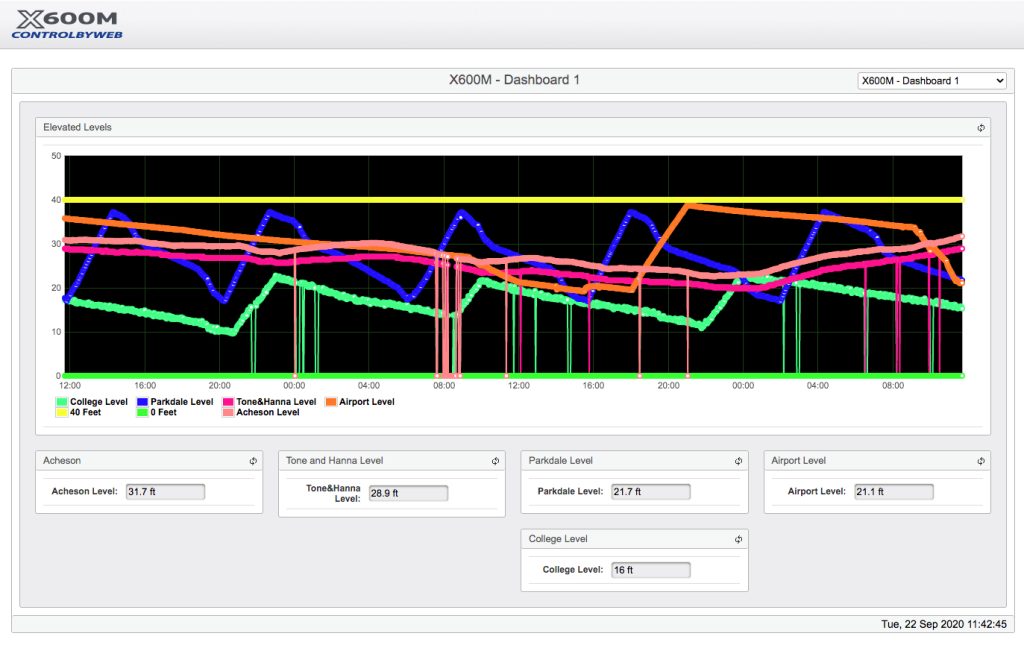

Evans set out to find a SCADA control system that they could program themselves, making modifications and maintenance much faster and far more efficient. He also wanted to save his town some money. By focusing on the simplest solution to his plant’s problems, he found ControlByWeb programmable I/O controllers that he and his crew could easily operate without code and that also worked with their existing equipment. The simple display interface acts as their SCADA by giving them graphs of each process variable from level and flow to turbidity and pH.

SCADA Graphs

The Randell Water Treatment Plant is now running on the X-600M platform with various expansion modules and I/O devices. The control system was installed in the fall of 2017 and the total cost was around $10,000, a 90% savings from their original budget.

The system solves the very issues cited by the American Society of Civil Engineers for rural water plants:

- Low Cost

Financing was a pleasant surprise rather than a bureaucratic battle. - Easy to Manage

The X-600M system worked with existing equipment and fit right into their plant. - Low Technical Requirement

Water plant operators only need basic electrical wiring and device networking skills. No coding needed.

If rural America is to find ways to improve water quality, it’s going to have to focus on the simplest way to solve specific problems. Saving money on control systems is one way to free up capital for new and improved equipment that will help bring small or low-income water systems into compliance.

Hope for a Cleaner Future

There is hope on the horizon. In May, 2020, the USDA announced a $281 million investment in rural water projects throughout 36 states and Puerto Rico. Non-profit organizations like Dig Deep run initiatives like the Navajo Water Project. These projects help the most under-served members of our society by raising millions of dollars to put clean, hot and cold running water in U.S. homes. There has also been more national attention given to the need for increased funding for infrastructure improvements and water quality.

The road ahead has plenty of challenges, but it’s also full of opportunity. People who work in non-profits, legal, water treatment, and regular citizens who raise their voices are everyday heroes. They’re finding ways to improve water quality by creating new funding sources, by spending less capital, and by inspiring others to get involved.

Technology has been moving at a rapid pace and that’s helping to solve some of the world’s toughest problems. By combining these advancements with prudent oversight, and with the help of private organizations, governments, and non-profits, we can help bring an end to the American water crisis.

If you’re working on a water quality project and you need affordable, industrial-grade process controllers, speak to our application specialists to understand how ControlByWeb can be a good fit for you.